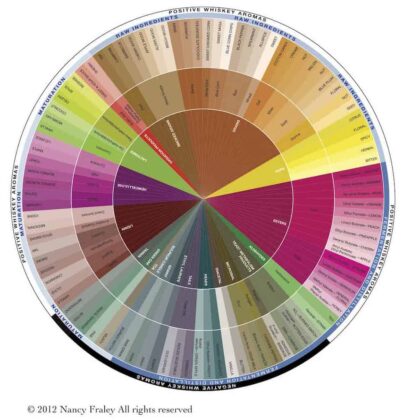

For the past two and a half years Nancy Fraley has been independently developing an aroma wheel tailored solely to meet the needs of the American craft whiskey industry. It is designed as an aid in assessing the various positive aromas and negative off notes derived from raw ingredients, kilning of malt, fermentation, distillation and maturation. ADI expects to offer the first American Craft Whiskey Aroma Wheel to members in autumn 2011. — Ed.

It is extremely difficult to capture, classify, describe and standardize whiskey aromas from an objective, analytical standpoint. Though the production of whiskey is as old as the wheel, getting the intricate array of whiskey-derived aromas to fit neatly within a wheel’s spokes is a problematic task. This dilemma can be seen with the range of new American craft-produced whiskeys currently on the market. The raw ingredients of many of these boundary-pushing distillates come from cereal grains, such as oat or spelt, that have not been used traditionally for whiskey production. Woods such as cherry, alder and beech are often being used to smoke malt during the kilning process, adding to the sensory complex. And increasing experimentation with hops in whiskey can add yet another level of aromas to the mix. While these new flavor profiles create excitement for the consumer and connoisseur, they present an enigma for the sensory analyst. The increasing use of non-traditional raw ingredients and production techniques that help create these unique sensory profiles requires a radical rethinking of how whiskey aroma is categorized in a systematic, standardized way.

The Scotch malt whisky industry began this laborious process of categorization of whiskey odors in 1979 with the development of the Pentlands Flavour Wheel. This wheel, since revised, was created by chemists at what is now known as the Scotch Whisky Research Institute as a tool to aid in the evaluation of spirit within the industry. In addition, there have been other aroma wheels, such as the Dewar wheel, Charles Macleans Whisky magazine wheel, and the Macallan wheel, all of which are directed mostly towards Scotch malt consumers.

A typical feature among many of these whisky flavor wheels is the use of a two or three-tiered structure, employing primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of odor analysis. The primary tier usually consists of the most general industrial aroma terms to classify odors, such as “fruity.” The secondary tier features more specific sensory descriptors to classify the odors even further. Thus, for example, this level of terms would classify the descriptor “fruity” by differentiating between “citrus” or “dried” fruit. The third tier, when employed in aroma wheels, uses the most specific sensory descriptors. At this level, “citrus” could be broken down into “orange peel,” “lemon peel,” as “dried” could be broken down into “fig” or “date.”

All of the wheels created by and for the Scotch whisky industry have one thing in common — they address the aromatic components of whiskeys made from only one type of grain, barley. On these wheels, the primary tier descriptor for the odor of malted barley might be “cereal,” with the secondary tier odor descriptor being “cooked mash.” A more specific third tier descriptor would assess the odor as “biscuit,” or “bran.”

As good a tool as these wheels are for assessing Scotch malts, their usefulness as aromatic reference tools begins to erode when confronted with whiskeys made from other grains. The North American continent has long been producing whiskeys that incorporate rye, wheat, and corn into the mash bill. No aroma wheel has been created so far to describe the odors derived from these traditional American whiskey cereals.

“The organoleptic conundrums do not stop with assessing the basic raw ingredients.”

To complicate matters, craft whiskey distillers have a whole range of alternative grains to the mix, such as blue corn, spelt, oat, millet, quinoa, buckwheat and sorghum. Because of this, it is no longer adequate to describe the “cereal” component on a whiskey flavor wheel as smelling like “cooked mash,” or as having a “bran” aroma. What does cooked blue corn smell like? Or cooked millet? What are we to do when confronted with the aromatic complexities derived from combinations of different grains in the mash bill? Or with the aromas that can be derived from a range of brewers’ malts and roasting levels? And finally, are the odors derived from these alternative cereals so inherently different from those that come from malted barley that they deserve their own category on a flavor wheel?

The organoleptic conundrums do not stop with assessing the basic raw ingredients. Outside of the smoky notes derived from the interaction between distillate and barrel toasting or charring, Scotch malt whiskey aroma wheels have only had to describe the phenolic aromatic components derived from kilning malted barley over decayed vegetation matter. Thus, first tier aromas might be described as “peat.” Second or third tier descriptors often refer to these phenolic aromas as “smoky,” “tar,” “medicinal,” or “kippery.” When these traditional flavor wheels are used to assess American craft whiskeys whose malts have been smoked with woods like cherry, alder, beech or apple, many of these phenolic descriptors no longer apply. How exactly is the cherry wood aroma different from apple, or from peat? One craft whiskey producer even uses Texas scrub oak to flavor their whiskey. How can this aroma best be described in precise, objective terms when most palates are unaccustomed to anything like it?

A few artisan producers have been experimenting with the use of hops to give their whiskey a distinctive top note. Hops, as brewers know, can give off a range of aromas from bitter, floral, grapefruit citrus, spicy to herbal. On traditional Scotch malt whisky wheels, these categories are usually shown as being derived during the production process as a result of ester formation, yeast strains, barley lipids, fatty acids, etc. So in an American craft whiskey aroma wheel, does hops get a category of its own? Is there a real distinction to be drawn between the floral-citrus sensory qualities of hops and the floral-citrus aromas derived from the fermentation and distillation process? If so, how are these aromas best categorized in a useful way on an aroma wheel?

To take the addition of aroma another step further, a few distillers are beginning to produce flavored whiskeys, such as apple, peach, or pumpkin spice. While this practice has certainly yielded some interesting results, I have not included the aroma profile of such whiskeys in the American Craft Whiskey Aroma Wheel.

Many craft whiskey distillers are using small barrels in order to increase the surface area to volume ratio of distillate to oak. Since whiskey aroma wheels have been geared towards the Scotch malt industry, traditional maturation categories on these wheels have assumed that barrel-aged odors will derive from standard sized previous use Bourbon or sherry barrels, or from various cask-finishing regimes such as port or Madeira. While many of these aroma wheels allow for a “new wood” category, which might be dissected further into second and third tier terms such as “astringent,” “sawdust” or “resin,” do these existing categories adequately describe the range of aromas derived from the practice of maturing whiskey in small barrels? The evaporation of volatiles such as ethyl acetate and acetaldehyde, and the extraction of wood sugars, tannins, lactones, vanillins, acetic acid, etc., is primarily a function of time with the slow exposure of the distillate to oxygen. Arguably, the shorter time allowed for maturation in small barrels will not yield the same “matured,” “complex” aromas that a whiskey matured in a 53 gallon barrel would have. How can these “immature” aromas best be described in more specific terms? And are they necessarily an undesirable attribute to everyone?

Finally, some craft whiskey distillers are employing the use of wood chips or inserts into their barrels to augment the oak notes in their distillate. And a few distillers are experimenting with different types of oak, such as Quercus garryana, or Oregon white oak. This species has been known to impart cinnamon and bacon-like notes into the spirit. A few have even ventured into employing French and other European oak species into their maturation programs, giving their whiskeys more complex, spicy notes instead of the highly aromatic coconut aromas found in American white oak lactones. What types of qualitative sensory differences do such whiskeys have from ones aged in more traditional ways with Quercus alba? And if there are significant aromatic differences, do current Scotch whiskey aroma wheels already account for these sensory qualities?

These are just a few of the questions that I have wrestled with in the making of the American Craft Whiskey Aroma Wheel. In the construction of such a wheel, there are no easy answers, and it is certainly far from perfect. However, I hope it will be the beginning of a constructive, on-going dialogue on the ever-expanding sensory color palette that is being drawn by craft whiskey distillers, and that it will be of pragmatic use within the industry. I am currently in the process of producing two other aroma wheels for the American craft brandy and rum industries. A “cereal” wheel for alternative grains is also in the works.