John Dewey

Education, teaching and discipline are lifelong social phenomena and conditions for democracy, according to acclaimed American philosopher John Dewey.

The man behind the words is the American philosopher, educator and social critic John Dewey, who all the way back in 1887 wrote his first pedagogical article My Pedagogic Creed, and whose pedagogical thoughts have since been known worldwide.

Education is life itself

One of Dewey’s ideas about teaching and learning is that practical problem solving and theoretical teaching should go hand in hand. This idea has had a huge impact, especially among teachers in the USA. In Denmark, his way of thinking inspired the school system to such a degree that Denmark has been called Dewey’s second home country.

Furthermore, Dewey was sought after in countries like China and Soviet where he was used as a pedagogical consultant.

However, Dewey’s pedagogical philosophy is not just about learning by doing. According to Dewey teaching and learning, education and discipline are closely connected to community – the social life. Education is a lifelong process on which our democracy is built. As he put it: “Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.”

According to Dewey, democracy and education are two sides of the same coin. Both involve and foster self-determination, self-development and participating in the common good, enlightened by intelligent understanding and scientific spirit.

Children are not listeners

Dewey was pragmatic and in no way did he agree with the romantic Rousseau that “the untainted nature of the child should be protected from the depraving influence of culture.” Not only did this position make him contradict the traditional concept of learning – it was also going against progressive anti-authoritarian pedagogy.

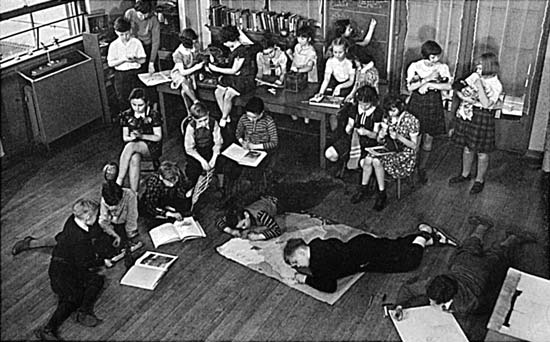

Traditional schools with practical learning by passive reception he described as “medieval”. Partly because it submitted pure intellectual, detached knowledge that belonged to the past – and partly because it was based on the inaccurate assumption that children are listening creatures. “But they are not,” Dewey emphasised. “Children are first and foremost interested in moving, communicating, exploring the world, constructing and expressing themselves artistically.”

The teacher is the master

Furthermore, he criticized the school for counteracting the children’s ability to corporate, because it was considered “cheating” and “copying”, if the children helped each other. On the other hand, he wasn’t a follower of the anti-authoritarian pedagogy, which in his opinion tended to see any form of pedagogical leadership and guidance as an intervention in the individual’s freedom.

On the contrary he declared that authority is a pedagogical condition for the individual’s development. Of course, he didn’t mean the outer authority of the traditional school, but the one of the “modern human knowledge and skill.”

“Humans learn through relations to more proficient people, who become a role model. Not by being left alone. Hence the need for more guidance from others than in the traditional school,” he said. He explained his view of teaching as a sort of apprenticeship, where the teacher was the master.

Learning life skills

In 1896 Dewey founded an experimental school at the University of Chicago. It was shaped by “what the best and wisest parents want for their children.” In Dewey’s opinion that had to be what the community would want for all their children.

Dewey’s own children attended the school and in 1902 – when the number of pupils was at its highest – it had 140 students and 23 teachers, who were occupied with the core of the school’s teaching: Chores.

According to Dewey, chores are “an activity with the child that reproduces, or runs parallel to, a sort of work being done in the social life.” That meant activities such as wood work, cooking, sewing and other activities necessary for sustaining life, which combine the child’s experience from its own intimate world with the practice of society – what we today know as “life skills”.

Good judgement

In a Dewey school the stereotypical gender roles are discarded. Girls participate in crafting equally to the boys, who have as many cooking classes as girls.

However, the children are divided by age, where the youngest do what they know from their home. The six-year-olds build a farm of blocks and plant crops they process.

The seven-year-olds study prehistorical life. The eight-year-olds are occupied by exploring, the nine-year-olds geography, and the older ones by scientific experiments within anatomy, physics, political economics and photography.

Dewey thought that this type of practical learning combines more learning recourses than any other method. Partly because you do something, partly because you do it together and thereby acquire social interest and moral knowledge.

The goal is to make the children want more teaching. That is the only way democracy can function as a lifeform, Dewey thought. And the ultimate goal is to create human beings with good judgement, who can participate in the community to discover the common good.

And how could anyone possibly be against that?

Still controversial!

Dewey’s views on pedagogy and politics are still considered controversial. In 2005, a conservative think tank with scientists from Princeton University among others, had the task of specifying the most harmful books from the 19th and 20th century. Dewey’s “Democracy and Education” came in fifth, only surpassed by “The Communist Manifesto”, “Mein Kampf”, Mao’s “Little Red Book” and Kinsey’s “Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male”.

What is Pedagogy for Change?

The Pedagogy for Change programme offers 12 months of training and experiencing the power of pedagogy – while you put your skills and solidarity into action.

Studies and hands-on training takes place in Denmark, where you will work with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools with a non-traditional approach to teaching and learning.

In short:

• 10 months’ studies and hands-on training in Denmark, working with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools. At the same time yo will study the world of pedagogy with your team – a group of like-minded people. You will meet up for study days every month.

• 2 months of exploring the reality of communities in Scandinavia / Europe, depending on what is possible – pandemic conditions permitting. You will travel by bike, bus or perhaps on foot or sailing.

• Possibility to earn a B-certificate in Pedagogy.

How to tackle intolerance

Being an active bystander means becoming aware that inappropriate or even threatening behaviour is going on and choosing to challenge it. Collective action is the way forward.

Mónica shares her experience

Mónica just finished the Pedagogy for Change programme and we asked her to share some of her considerations and main takeaways from her experience of practising and studying social pedagogy in Denmark.

“Zone of Proximal Development” exemplified

In this blogpost, we exemplify how the theory of the “Zone of Proximal Development” can be implemented in real life when working in the field of social pedagogy.

MORE GREAT PEDAGOGICAL THINKERS

Axel Honneth

Through recognition, human beings develop self-confidence, self-respect, and self-esteem. The theory of recognition was developed by German philosopher and educator Axel Honneth.

Astrid Lindgren

Astrid Lindgren’s thoughts about children were provocative in the 1940s, and her approach to childhood as a phenomenon is progressive, even today.

Lev Vygotsky

Interaction with peers, imitation, collaborative learning and other social interaction is key to how the human mind develops, according to Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky.

Maya Angelou

In times of injustice and hardship, Maya Angelou’s call for humanity, unity and resilience teaches us many important life lessons. Her works inspire hope through action.

James P. Comer

“No significant learning can occur without a significant relationship.” Really? Does Dr. James Comer mean that students need to be close to their teacher to learn something?

Jean Lave

Jean Lave is a social anthropologist and learning theorist who believes that learning is a social process, as opposed to a cognitive one – challenging conventional learning theory.

Søren Kierkegaard

Making choices and taking action are at the very core of existentialism. By taking on these responsibilities, as human beings – we find the meaning of life.

Maria Montessori

Children prefer to work, not play. This is one of the main ideas of Maria Montessori, a trailblazers of early childhood education. “The child who concentrates is immensely happy” she noted.

Sofie ‘Rif’ Rifbjerg

Brought up in the countryside Sofie Rifbjerg knew intuitively that fresh air, free play & a deep respect for children’s own agency was paramount for their positive development.