There are two water stains on the ceiling here. The first one is clearly the silhouette of a man with a bulbous head viewed from behind. I don’t pay much attention to this one. The other stain is far more interesting. At the top left, there are two small spots gathered closely together; at the bottom right, one large spot. That’s all there is. There’s nothing about the stain that suggests a face, and yet it’s a face. The two small spots are the eyes, beady and imbecilic, and the large spot is the mouth, which is puckered and twisted far to one side. The effect is quite unsettling, as if the face represents a soul undergoing infernal torments, or a body whose molecules have become distended through contact with a black hole. Either way, it is the expression of a being on the verge of total dissolution, too thunderstruck even to recognize the agony it’s in. When I first noticed it, it was merely a stain—a gathering of unsightly splotches in ocher and sepia—but now that it has become a face, it can never be anything else. It’s as if my mind becomes hypervigilant at the idea that there may be faces nearby. When in doubt, it always seems to err on the side of there is a face here, watching me.

I’ve been in the isolation ward since my checkup three days ago. I’d been experiencing some aching and fatigue and was afraid that I might have acquired toxoplasmosis from cleaning up after my landlord’s six cats. While the doctor quickly ruled out this theory, he decided to give me a chest X-ray, which revealed a small spot on my lung. It was at this point that my ordeal began. As far as I can gather, they think I have tuberculosis.

I’m connected at the wrist to a plastic bag filled with high-octane antibiotics, and there are these inflatable, Velcro things strapped to my legs for some reason. I’m so burdened by medical gear that they’ve given me a clinical jug to piss in. It’s even got little lines and numbers embossed on the plastic (to measure my piss, I guess). The nurses wear special smocks, masks, and gloves when they attend to me, as does the doctor. They all knit their brows while in the room, and I can see in their begoggled eyes that they resent me for having potentially contracted such an anachronistic disease. On the other hand, there is also the sense that they don’t believe I have TB, and that all their fussing is meant to teach me some kind of lesson; to make sure I never do this again.

Do what?

They’ve finally moved me into a regular hospital bed to finish my cycle of IV antibiotics. It turns out that all I had was a simple case of aspiration pneumonia, probably from inhaling vomit particles. This makes sense. I’ve always had a weak stomach.

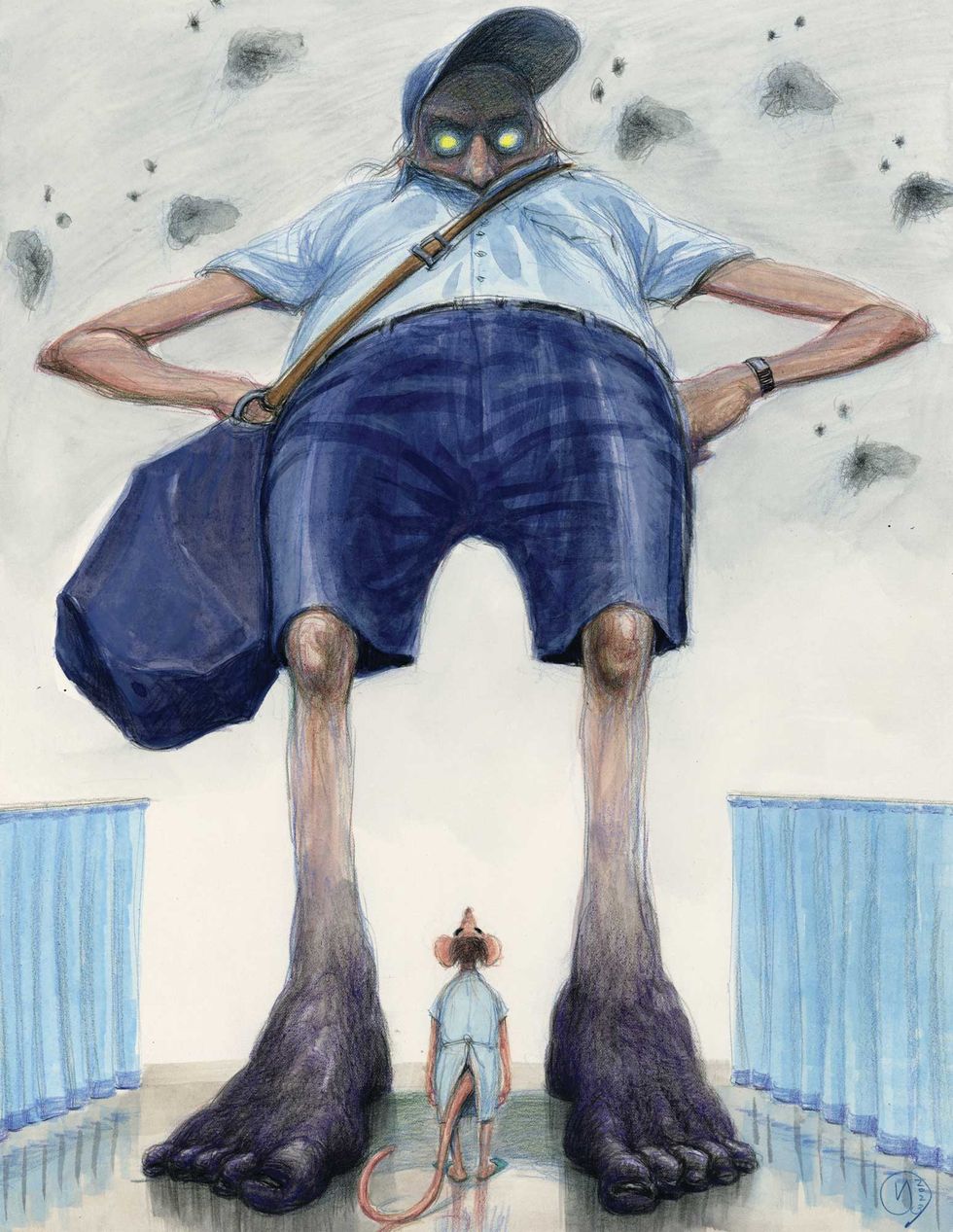

I have a roommate now. I’ve only been here a few hours, and already I’ve begun to pine for the peace of my former seclusion. I do not know my roommate’s name. The staff calls him only “the mailman.” The mailman is rude and obstreperous, continually demanding Budweiser and boiled eggs. I think he’s dying. For one thing, his feet have turned coal black (gangrene secondary to alcoholism and diabetes, the nurses whisper). His feet were the first part of him I saw, peeking out from the edge of the curtain that hangs between us. It looked like he was wearing socks made from someone else’s charred skin. From what I hear through the curtain, the blackness has receded from knee to ankle level since he was first admitted. The nurses are very encouraging about this, even though it seems clear to all concerned that the mailman is not long for this world.

This story appears in Issue 25 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

Today the mailman came through the curtain and approached me. He shuffled over to my bed in a Hawaiian shirt, flip-flops, and his standard-issue postal shorts (he vehemently refused to wear a hospital gown). His feet were a mess, and his greasy ponytail smelled faintly of decaying plant life. I lay motionless on my bed, struggling to keep down my French toast sticks.

“You seem pretty young to be in here,” he said. “What are they holding you for, anyway?”

I told him.

“Drugs, eh?” he said smugly.

I hadn’t said anything about drugs. I tried to correct him, but he seemed to believe he was calling my bluff. I got the sense that this was the conversation he had planned on having no matter what I said.

“You know what they say: jails, institutions, and death. That’s where that stuff gets you. Believe me, I know,” he said, practically shouting. “You’re already in a hospital. If I were you, I’d quit while I was ahead.” He looked me over for a moment. “You don’t strike me as somebody who’d do very well in jail.”

Up until that point, I hadn’t really been listening to him. But something about this last comment made my ears perk up, if only for a moment. Pretty soon, I was back to staring at his feet. He went on to talk about a stint in county jail he’d done in his youth. I’ve already forgotten most of the details, but I remember distinctly the funny way he had of holding court and sounding exasperated at the same time, as if I were compelling him to talk about these things against his will. He just kept jabbering and staring at me with his strange yellow eyes, swimming in his oversize Hawaiian shirt like a mummified Jimmy Buffett.

I learned today that I’m still covered by my father’s insurance plan even though he died earlier this year. This is a huge relief, as my stay here would probably have wiped out the remainder of my inheritance. My father was 61 when he died. Not young, but too young to die. However, there were several relatives at the funeral muttering about how he was too old to have died the way he did (mouthing off to some young veterans in a bar, challenging them to a fistfight, and going to bed that night with a ruptured spleen). It’s too bad my father’s life ended the way it did, but it was just one of those things. For what it’s worth, I know he went to bed that night feeling proud. He came home singing. I’m sure he won that fight. One of his opponents got in a lucky punch, that’s all.

Today the mailman left, against medical advice, to attend his niece’s wedding. He insists he’s coming back, but both I and the nursing staff assume he’s lying, deploying the first excuse he came up with so he could go home and ride his old habits into the grave. The thing about the wedding may have been true enough, but the importance he placed on his presence there was almost certainly exaggerated. Surely his loved ones would have understood that his health was more important. Moreover, he didn’t strike me as anyone’s beloved anything.

After he left, the nurses used the mailman’s departure as a cautionary tale for me. He must have told them that I was a drug addict, which was, of course, a fabrication. The nurses affirmed that he faced certain death and implied that the same fate would be awaiting me if I should choose to flee. Even taking into account that their warning was based on a false premise, their logic still didn’t make any sense. They knew as well as I did that the mailman was going to die whether he persisted in his habits or started attending 12-step meetings for his remaining months. Doctors, nurses, family, friends, fellow patients—there wasn’t a living soul who didn’t know in his heart of hearts that the mailman’s stay at the hospital was pointless. The mailman himself knew it better than anybody, as his flight made clear. But they all had to encourage him just the same. What a charade! Who was it all for?

Having the room to myself was a relief at first. However, I still feel the mailman’s presence. The curtain is drawn around his bed and, though I know it’s empty, I can still picture him lying there, stewing, biding his time before his next volley of grievances.

More than anything else, it is his jail comment that sticks in my craw. How the hell did he know how I would fare in prison? He’d known me for all of two minutes when he pronounced this judgment. I can’t believe this was his first impression. I’ve been going through life with the assumption that strangers credit me with a certain degree of fortitude, or at least give me the benefit of the doubt. I’d never framed it in terms of prison, of course. But, come to think of it, I’ve always hoped (without knowing I was hoping) that people would think of me as somebody who would do very well in jail. Had I been wrong all this time? Did everybody else see what the mailman saw? If so, I have a huge problem on my hands. Other qualities are valuable, sure—patience, reason, empathy, humility, persistence, etc.—but let’s face it, if you don’t project an air of dominance, all the rest of it is worthless. Even animals know.

The mailman’s comment was like the stain on the ceiling of the isolation ward—a collection of meaningless symbols coalescing into an appalling form that, once seen, could never be unseen. My only comfort lay in the certainty that the mailman would be dead soon. Maybe it was foolish, but I had the distinct feeling that his perception of me would be buried along with his gangrenous corpse.

The idea of cremation brought still more comfort.

Today they let me go home. The nursing staff wished me well, sending me off with a bottle of enormous antibiotic tablets and a number of brochures for NA and the like. It didn’t seem worth it to tell them I wasn’t a drug addict. They would have assumed I was lying, or that I had yet to overcome my denial of my alleged problem (the first of the 12 steps, according to the brochures).

Because of my hospitalization, I had been unable to take care of my landlord’s cats for a few days. He even had to postpone his latest business trip, on which he was supposed to hock foot massagers at a string of trade shows across the Southwest. He was not shy in informing me about the profits he was missing out on, and this was reflected in a rent increase for that month. It always made me wince to watch my inheritance dwindle ahead of schedule. On top of that, he didn’t even stock the pantry with cat food, and he left the litter boxes full (gestures of spite, no doubt).

After emptying the litter boxes, I drove to the supermarket to replenish the cat food supply using even more of my inheritance. Despite the financial hemorrhaging, it felt nice to glide through the aisles, mostly empty at midday. The high ceilings, ample air-conditioning, bright lights, and sublimely vacuous pop music charged me with feelings of optimism. There is nothing like convalescence to make the asinine things in life appear hopeful, if only temporarily.

As I approached the only available checkout lane, a large young man in athletic clothing and a backward baseball cap shot in front of me carrying a case of beer and a bottle of upmarket vodka. He looked like somebody who might be in the porn business. He stared directly into my eyes.

“You don’t mind if I scoot in front of you, do you, boss?” he asked.

I did mind. This was outrageous.

“No. Go ahead,” I muttered, stupefied. As I stood there, waiting for him to make his purchase, my cart laden with a preposterous quantity of Fancy Feast, I thought about the mailman. This encounter seemed proof that his observation was not anomalous. This buffoon saw it too. It was plain as day. I was a man beholden to a half dozen house cats. Pussy whipped, as it were. It was no wonder this meathead felt comfortable humiliating me. And I played my part beautifully, even returning his wave as he got in his truck and drove away. A man who would do very well in jail would have followed him to the parking lot and stabbed him.

In the year I’ve spent at my current place, I haven’t encountered my landlord often, but when I do, the conversation always leads him to extol the merits of the foot massagers he sells. This never fails to puzzle me. I remember when he began selling these products. He chose massage equipment because it was the most profitable choice, not because of some conviction he had in the company’s vision. He knew I knew this, but that didn’t stop him from trying to sell me on the inherent virtue of the Medi-Rub corporation. At a certain point, it became clear that he wasn’t playacting anymore, but truly believed in the downright miracle of the massagers. He must have given the spiel so many times that he now believed it himself. Or maybe at some point, he made the conscious choice to believe it, as this made his life more meaningful, his sales pitch more jubilant, and his profits more substantial. Lately, I’ve begun to wonder whether or not I’ve been deluding myself in the same way. I’ve been running the mailman’s comment in my head for so long, it has begun to feel like truth. Perhaps the comment had no truth to it whatsoever. Perhaps the mailman’s brains had turned to mush from pissing his life away one Budweiser at a time. It was silly for me to credit him with such infallible insight. Any corroboration I found on the street was merely a projection of my own insecurities onto strangers who were, in all likelihood, oblivious to my existence. Once again, my mind has created faces where there were none. Besides, the mailman must certainly be dead by now.

The mailman is not dead. I sighted him by chance through the window above the litter boxes. By all appearances, he has gone back to work. He looked about the same, minus a few details—no Hawaiian shirt, no flip-flops. Instead, he was wearing his official postal carrier’s uniform with black shoes and socks that, from this distance, resembled his disease-ravaged feet. I had been so sure of his demise that seeing him back at work gave me the dizzying sensation of having seen a ghost. I walked downstairs and approached the large front window to get a better look. Sure enough, there he was, his face wan and sullen, his rattail protruding from a blue cap. At the sight of him, all the things I had said to reassure myself went down in flames. He was the living embodiment of the comment, a walking reminder of my secret shame that, until very recently, even I had been ignorant of. On some level, I knew that what he had said was nonsense, but as long as the mailman thought it was true, it would be true, since we weren’t dealing with reality but with hypotheticals. This was not about what I had done but about how I seemed, and seeming was the domain of the beholder, not the beheld.

The worst part of it was, I couldn’t think of any way to prove him wrong.

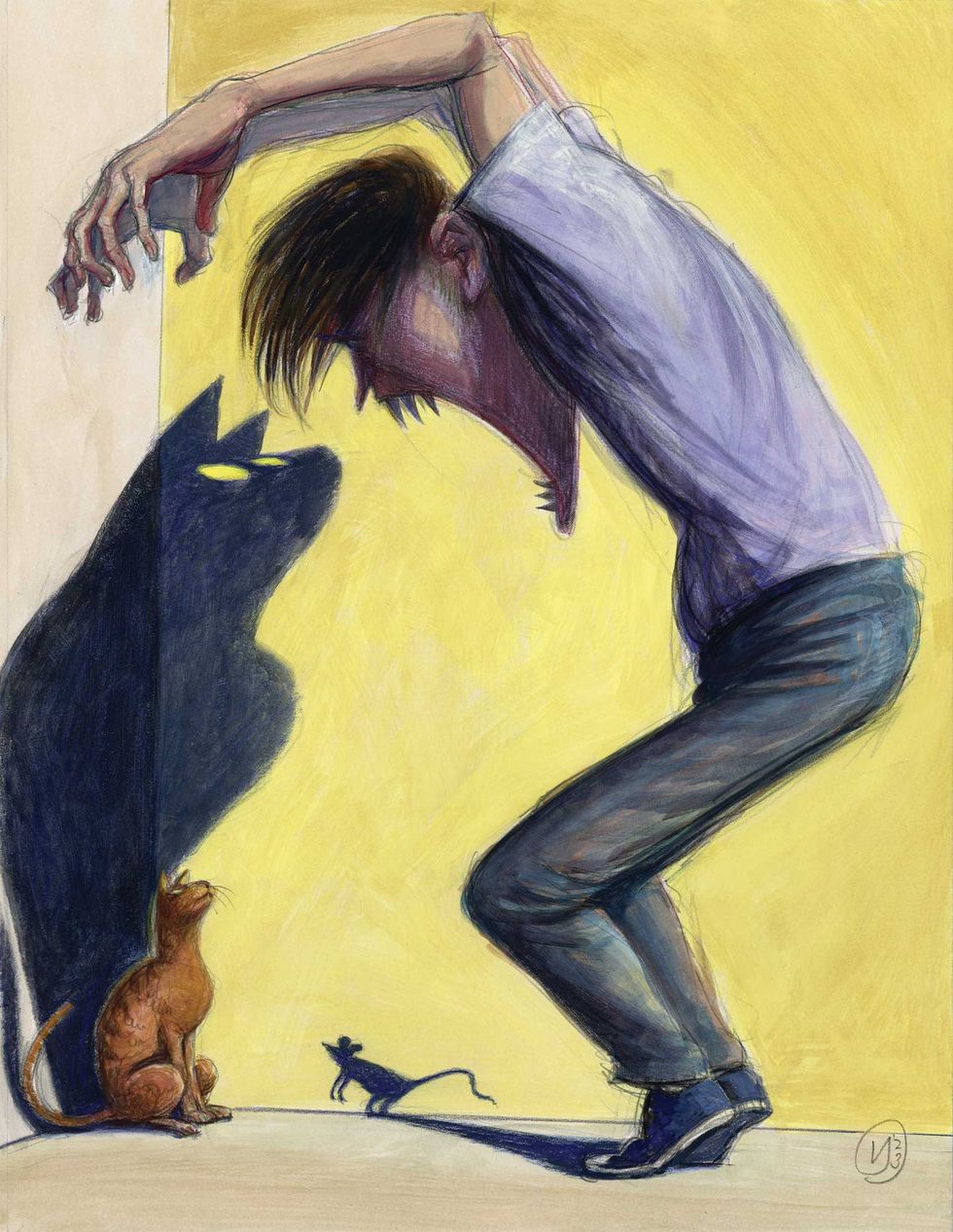

I have begun chasing the cats around the house. I leave some food on a plate, then hide in the pantry. Once they approach, I raise my hands over my head and form them into arthritic claws. Then I advance on the cats, slowly at first. They seem quite convinced that I have become a monster bent on devouring them. I chase them all over the condo, up and down the stairs, into the master bedroom, where my landlord sleeps, wherever. The whole thing makes me feel fearsome and powerful. Even outnumbered six to one, I know I could destroy every creature in the house if such was my will. It even makes me feel power over my landlord, who ordinarily exerts a great deal of control over my homelife, and whose bed is much larger and nicer than mine.

The fun ends once a cat has been cornered. I’m never sure what to do at this point. Looking into the animal’s eyes as it hisses in a last-ditch effort to repel me, I invariably realize the reality of my situation. Once the chase is over, I experience deep feelings of shame, at which point, overwhelmed by nausea, I back away from the animal and hurry to the bathroom to vomit.

Today I remembered something my father told me when I was seven years old. He taught me the importance of testing the limits of my scruples. A man who listens to his conscience all the time will never amount to anything, he argued. He believed that no progress ever came from cowards who kept to themselves and allowed others to dominate them. All the most powerful men knew this, he said, no matter how moral they made themselves out to be, no matter how much they told themselves and others that what they were doing was for the best. He told me that every president I’d ever heard of, even my favorite one, was a mass murderer. And you don’t get to be a mass murderer without testing the boundaries of your moral code.

As I turn this advice over in my mind, I realize how important it is that I continue terrorizing the cats while my landlord travels the country. Perhaps it can help me in unforeseen ways. This is how progress is achieved: by getting out of one’s comfort zone, by disrupting the status quo.

Today I drove to a bar by the harbor to pick a fight. I had never really been in a fight before, a fact that I am duly ashamed of. I stupidly admitted this to a girlfriend once. She looked incalculably dismayed, and although the relationship endured for over a year after that, I knew that my admission had dealt a fatal blow. It felt like it was time to remedy this situation once and for all.

The bar smelled like a sewer pipe had burst somewhere nearby. I ordered a beer and sat at a table near the corner. For the first 15 minutes or so, I simply observed my surroundings, trying to determine whom I should provoke. Although it pained me to admit it, the prime candidate was an apparent ex-convict built like a shipping crate whom all the regulars called Cordless. He sat at the bar three or four stools away from anybody, drinking boilermakers and staring at a huge jar of pickles. The operation was simple: I would stand behind him, wait for him to reach for a pickle, and kick his stool out from under him.

I have never felt the sort of fear I felt approaching Cordless. There was so much adrenaline coursing through my system that I had to down three drinks in rapid succession to steel my nerves. Once the alcohol took effect, my thoughts turned to my father. I was encouraged by the fact that I was taking part in his legacy. They say the children of suicides are more likely to take their own lives; maybe my willingness to follow in my father’s footsteps was related to this principle. Thus emboldened, I straightened up and marched toward Cordless, my eyes locked on the tattoo inscribed on the back of his neck: “peni death squad,” it read. As soon as he lifted up off his seat, I kicked the stool with everything I had. I don’t remember what happened next, but I awoke prostrate on the barroom floor with my left eye swollen shut and my front tooth broken where it had hit the ground.

In addition to terrorizing the cats, I have begun to eat their food. My stomach is getting stronger every day.

Today I drove to the nearest post office and parked my car in the parking structure where all the mail carriers drop off the trucks at the end of their shifts. I sat patiently and waited. After a few hours, the parking lot became filled with mail trucks. When there were only three spaces left, I began to worry that I had selected the wrong post office. I even considered leaving and putting this whole mailman business behind me. Then I saw an older model of truck pulling into one of the spots. From it emerged the mailman, his thin gray locks extending limply from the edges of his cap, the pitiful vestiges of his midcentury countercultural identity. He made his way to a 1970s Chevy Nova and drove slowly out of the parking garage. I pursued at a casual distance.

As I had anticipated, the mailman doesn’t live far from the post office. It turns out he’s more or less a neighbor of mine, living in a trailer park less than two miles from the room I rent. After he went inside, I lingered for a while, pondering. If I had been to jail, and had fared well, then I could have explained this to him. Yet surely there are people who have never been incarcerated who would carry themselves well in jail, given the opportunity. Perhaps I was one of these. The problem was making this known to the mailman. As I sat in my car outside the trailer park, I imagined how an unconvicted convict would respond to such an accusation. The answer was simple.

When I got home, I went straight to the kitchen to look for tools. From the top drawer, I fetched a crab mallet and a roll of electrical tape. I took the items to my bathroom and looked at myself in the mirror. There, I did not see the face of a craven milquetoast, a jailhouse bitch. I saw a fearsome individual. I saw my father’s son. I then cracked the corner of the mirror with the mallet and chose a narrow shard about six inches long. I wrapped the wider end with the tape, adding a thicker layer above that for a sort of hilt. I then rolled the whole thing in newspaper and placed it in my front pocket.

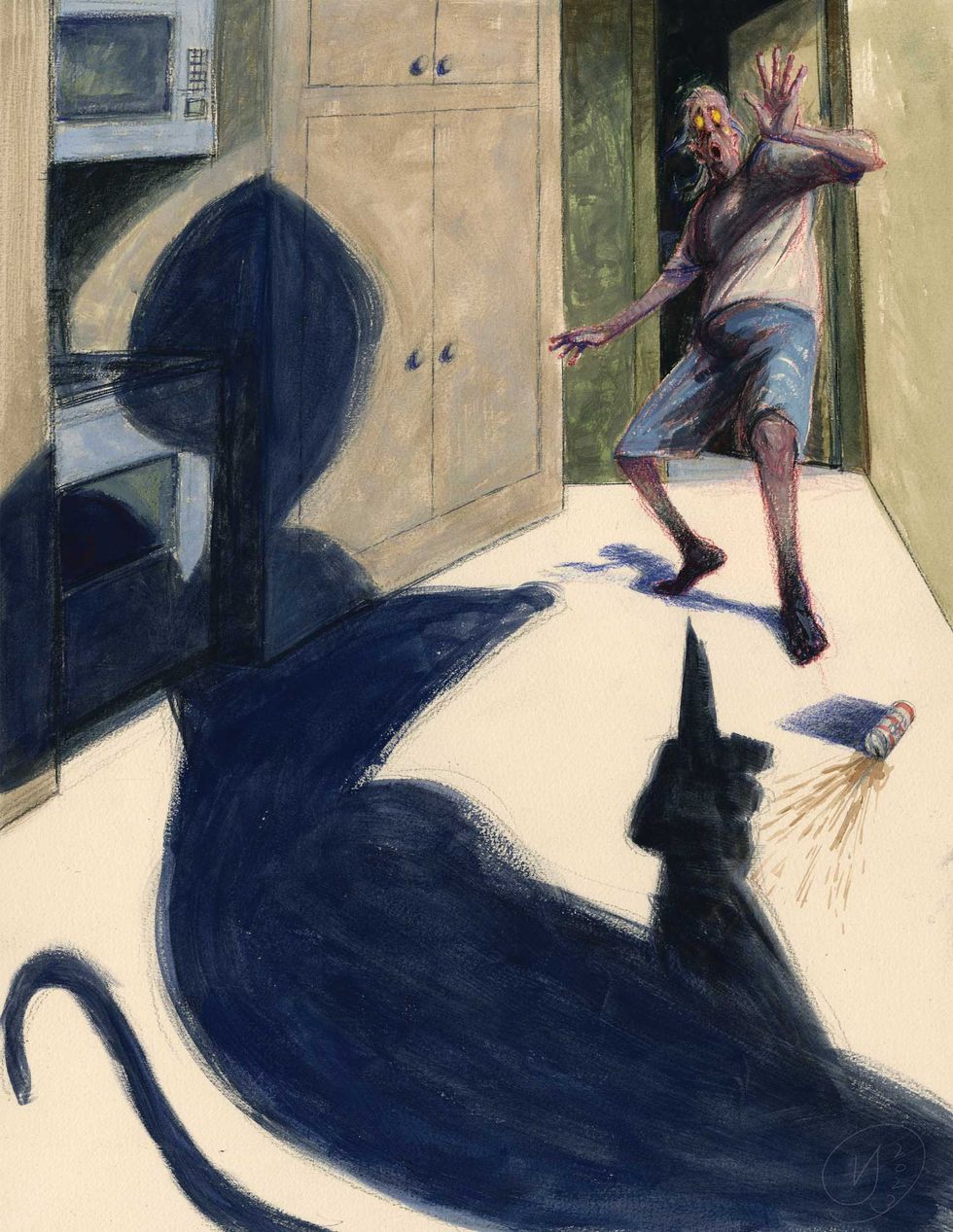

When I drove back to the trailer park, the lights were still on in the mailman’s unit. As soon as I parked the car, I moved swiftly toward his front door. I knocked loudly, but there was no answer. I knocked again, harder this time. I heard the mailman groan and begin moving toward where I stood. When he answered the door, he was bleary-eyed, clutching a Budweiser tallboy in his right hand.

“Well, what is it?” he drawled.

I stood there silently, unable to summon the wrath necessary to execute my objective, whatever it may have been. Much like my experience with the cats, I had no idea what to do with the mailman now that I had caught up with him.

“Do I know you from somewhere?” he asked.

I hadn’t anticipated that he might not remember me. This threw me a little, but then I began to think about his comment as I looked alternately at his yellow eyes and blackened feet. I was beginning to hate him again. I reached into my pocket and retrieved my shiv. Once I unwrapped it, the mailman began to panic.

“Hey, man, what is this? I don’t have any money, if that’s what you’re after, but you’re welcome to take whatever you need,” he said haltingly, gesturing toward an old lamp. Holding the shiv in front of me, I advanced toward him into the trailer. He began to run, knocking over furniture to impede my progress, but I pursued him steadily. The fear in his eyes was quite pathetic, and made me feel a little sick, but my practice with the cats had taught me that I could override this nausea. My father was right. I wonder if the presidents had to work their way up to ordering air strikes through some similar incremental shedding of personal ethics.

At the end of the main hall, there was a door. The mailman was running toward it as fast as his rotting feet would carry him. I ran after him with my shiv extended in front of me. He opened the door as if to enter the room, but at the last minute, he moved to the side and I tumbled into a bathroom. I heard the door slam behind me, followed by a loud thud. I tried to open it, but it was stuck. Even when I kicked it, it wouldn’t budge.

“You won’t get through this door, man,” the mailman yelled. “My old lady installed this barricade on the outside when she forced me to get off smack in 1979. I had nothing but tap water and Vienna sausages for six days!”

There he went, bragging again.

“Forget this,” he shouted. “I’m calling the cops. It’s too bad for you, man. You don’t strike me as the kind of guy who would do too well in jail.”

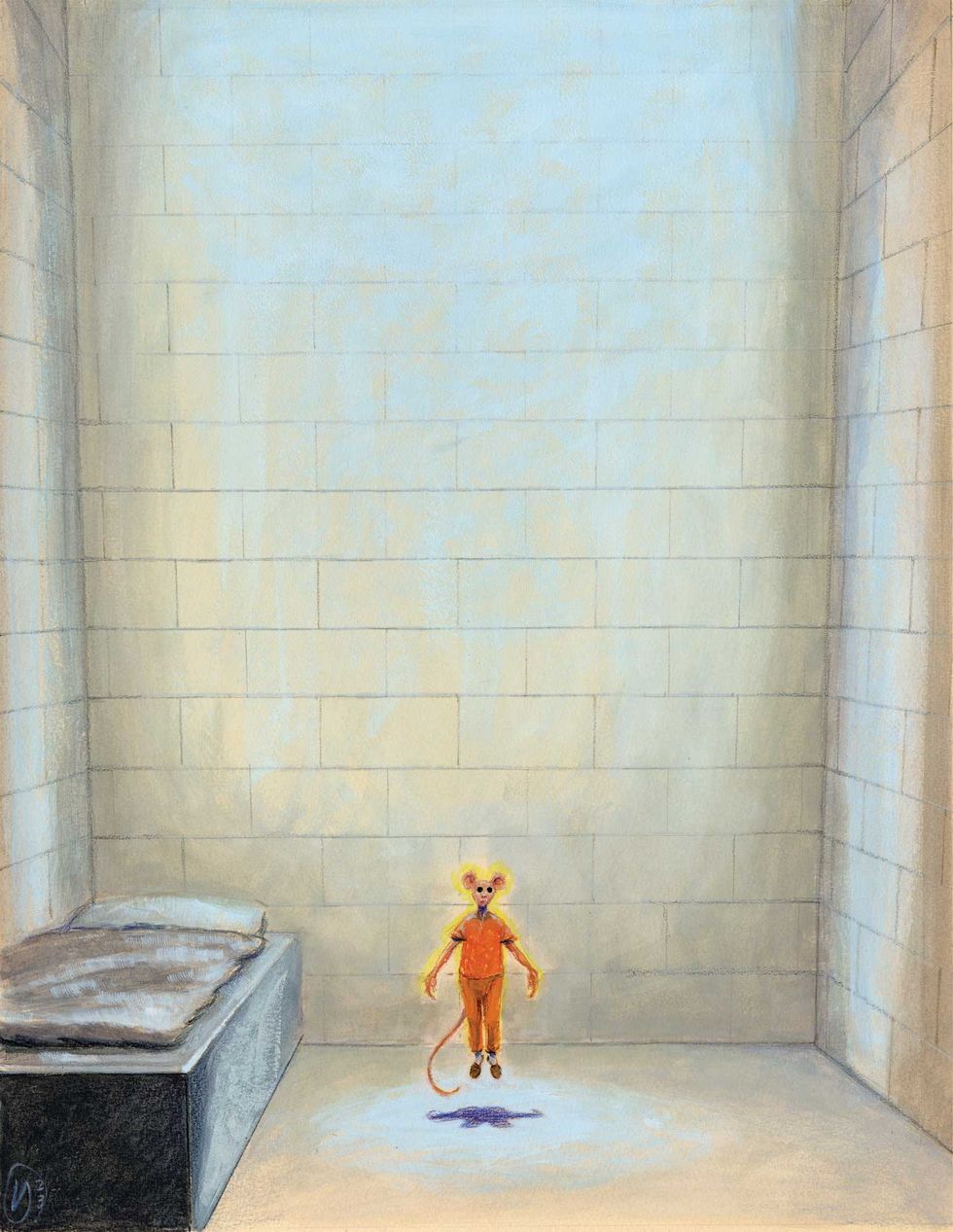

Since my arrest, I’ve been awaiting my trial in a six-by-nine-foot box with a bare fluorescent bulb that never turns off. Although nobody has explained the reasoning behind my placement in solitary confinement, my fear is that they have judged me to be too soft-looking to associate with the other inmates, which means they see in me exactly what the mailman saw.

Bereft of other options, I spend most of my time staring at the walls, but this offers only minimal distraction. The walls here lack the Rorschach effect of wood grain, and there are no stains like the ones above my bed in the isolation ward, only the regular geometry of cinder block and mortar, blanched to a white beyond white by the buzzing light bulb, whose reflected glare is strong enough to repel my eye entirely. Besides, when I stare too long at the walls, they begin to advance toward my gaze, or else they appear to topple. Shutting my eyes does nothing to alleviate this sensation. I am learning to sleep standing up with my eyes open. More than anything else, this seems to keep the walls at bay. Strangely, I have experienced no other hallucinations. There is simply nothing in my cell that provokes the imagination. I am unable to detect anything resembling a face.•

Andrew Hubbell is a fiction writer based in Los Angeles. He recently received an MFA in creative writing from California Institute of the Arts. This is his first time in print.