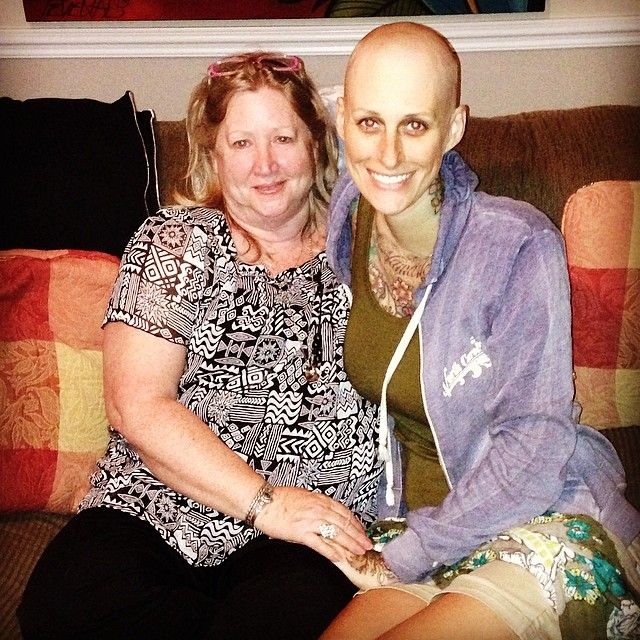

Beth Fairchild has been a tattoo professional for 20 years. But the work she does is anything but what most people expect. The 40-year-old specializes in areola tattoos for breast cancer patients who’ve undergone breast cancer reconstructive surgery.

Areola tattoos use color and shading to create an illusion of a 3D nipple protruding from the breast. They’re often sought out as an alternative to nipple restoration, a lengthy surgical procedure that some patients prefer to avoid. “Nipple restoration doesn’t always work or look very natural. It might also not be a good fit for patients with skin issues or skin trauma [from cancer surgery],” Fairchild explains.

Patients typically come to Fairchild around six months after undergoing breast reconstruction, once they’ve fully healed. “We’ll numb the area and select and mix the colors for the areola,” she says. “Then, I draw on the desired shape and size and tattoo the areola. The entire procedure takes about two hours.”

How she got her start

Fairchild’s connection to breast tattoos is deeply personal. When she was 20, her mother underwent a lumpectomy for breast cancer that resulted in the removal of half of her nipple. “She didn’t choose to reconstruct. Seeing my mom’s breast deformed from that procedure made me realize this is what breast cancer does to women. And I knew there was a need for this kind of tattooing,” she says.

Already working as a conventional tattoo professional for the past 10 years, Fairchild sought out specialized permanent cosmetics training, including areola restoration and scar camouflage. “I took the knowledge I got from the training and applied it to what I knew about skin and mixing colors, and I just started putting it out there,” she says.

Her early clients found her by word of mouth, and it wasn’t long before word began to spread. Now she’s a go-to specialist near the Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, area (Fairchild lives on the state’s coast), and hospitals in the region refer breast cancer patients to her.

From the start, Fairchild loved getting to know her clients and knowing that she was making a difference in their quality of life. “I love the intimate relationship that we get to create,” she says. “I love sending them away with this lasting thing and knowing that they’ll always remember the interaction.”

An unpredictable turn of events

Then life took a shocking turn. In 2014, Fairchild herself was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer (mBC)—stage IV breast cancer that can’t be cured.

Prior to her diagnosis, Fairchild had complained to her doctor about unusual abdominal bloating that had been going on for several months. Her doctor ordered a CT scan that revealed bone, liver, and ovary lesions. The scan also showed that her ovaries had grown to the size of grapefruits. Since they were on the verge of rupturing, Fairchild opted to have them removed.

When she woke up from surgery, Fairchild’s doctor told her that her enlarged ovaries and lesions were the result of breast cancer that had spread throughout her body—and it was worse than the scans has indicated. The cancer had spread to every part of her body, including her uterus, cervix, and the entire top of her vagina. “My entire pelvic cavity was fused with cancer, so they [had to take] everything out [during the surgery],” she says.

Two years left to live

Fairchild was told that she had two years to live, even with the best treatment options. She knew that she wanted to spend time with her family and travel as much as she could, but she also wanted to keep on working. Focusing on helping others through tattooing—along with breast cancer-related advocacy work she’d soon take on—drove her to keep moving forward instead of dwelling on her disease.

Not wanting to cast a shadow over her clients’ cancer journeys, Fairchild opted to keep quiet about her mBC at first. “They were coming to me because they had just experienced this thing, and my work was part of their healing process. I didn’t want to tell them that I had terminal cancer,” she says. But listening to clients with highly treatable, early-stage cancers open up about their struggles was hard.

“They’d talk about how they didn’t feel attractive anymore because of how their breasts looked. I thought to myself, If you knew the other side, if you were stage IV and you knew you were gonna die, you wouldn’t even care about what your breasts looked like,” Fairchild says.

Connecting with women she could relate to

Fairchild knew she needed to connect with patients like her, who were dealing with mBC. So she joined an online support group a few months after her diagnosis, where she was finally able to meet others she could relate to.

Getting involved with the online mBC community led Fairchild to take notice of the ways that some people strove to bring awareness to breast cancer. And she found a lot of the tactics to be frivolous. “Someone posted a pink tractor that they were taking around to raise awareness. So I said to the group, ‘The $60,000 spent on this tractor could have been used for research that would help people stay alive,’” Fairchild says. “As someone who’s dying, I’d forego all the support in the world for more research dollars.”

Becoming an advocate

In an effort to get the public to focus more on the need for mBC research funding and less on pink cancer-themed products, Fairchild launched the virtual protest Stomp Out BC. She and other mBC patients designed sobering graphics to clearly illustrate how much time each had left to live.

“One of them might have three Christmas trees or Easter eggs to represent the average number of holidays I had left,” she says. They began sharing the graphics in March 2015 on social media, tagging #DontIgnoreStageIV, and the movement quickly went viral, with the hashtag trending on both Facebook and Twitter.

Beth quickly became mBC’s best-known advocate, getting featured in magazines and on TV shows. She also accepted an offer to serve as vice president of the mBC nonprofit METAvivor. The organization is dedicated to increasing research on advanced breast cancer, as well as patient support.

“I never thought advocacy was my thing. But I knew how to tell my story,” Fairchild says. And people listened. “When I was first diagnosed in 2014, there was nothing about metastatic breast cancer anywhere. Now you can go to any advocacy group and they have a whole space for mBC,” she says.

That includes METAvivor. “We’re constantly publishing about new drugs, reliable resources, studies, and clinical trials, as well as sharing patients’ journeys, especially women of color who aren’t getting the treatment they deserve,” Fairchild says. And thanks in part to her efforts, the nonprofit raised $6.2 million dollars for mBC research in 2019 alone.

Beth’s role has changed since stepping into the advocacy space in 2015. Now a past president of METAvivor, she’s taken on a leadership role with the media platform #Cancerland, which uses photography and video to address breast cancer’s often ignored realities. “We’ll share our content on social channels and people will learn new things, like how an 18-year-old can be diagnosed with mBC or that women who still have their hair can have mBC,” Fairchild explains. “That helps us gain momentum and build donations.”

Marrying advocacy with art

While working as a spokesperson and storyteller, Fairchild has continued to do tattoos—and her relationship with her clients has evolved. “Now I’m open and honest about my mBC, and most of my clients come and find me because of that,” she says. “Now with someone I’m just meeting, we can talk about the most intimate details of our lives. And I automatically know they understand me and vice versa,” she says. “When I’m giving someone a permanent tattoo, it’s a big deal to have that kind of rapport.”

Six years after her diagnosis, Beth’s mBC hasn’t advanced. “I still have cancer, but it’s not doing anything, it’s just kinda hanging out. It’s pretty miraculous that I’m still alive and still healthy,” she says.

Arthritis caused by her cancer meds means her joints are always in pain and some days she needs more downtime than others, which can sometimes make it hard for her to work. But she vows she’ll keep doing what she can, for as long as she can. “I need something to work towards,” she says. “That’s what keeps me going. It keeps me hanging on.”

For information and resources on living with metastatic breast cancer or how to support someone who is, including a Treatment Discussion Guide, visit FindYourMBCVoice.com.