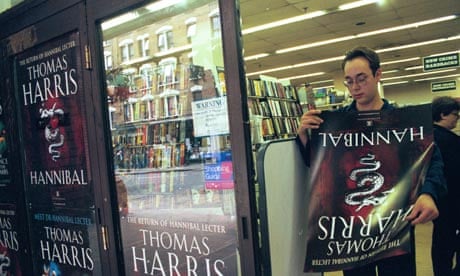

Is there another contemporary fictional character who exerts a more gruesome fascination than the murderous psychiatrist Hannibal Lecter? He is the defining Hollywood antihero of our times, with his own long and elaborately detailed entry on Wikipedia, and he returns early next month when his reclusive creator, Thomas Harris, publishes his first novel for seven years, and the fourth in the multimillion-selling Lecter series, Hannibal Rising, a prequel to the earlier books that follows Lecter from childhood to the age of 20.

Extraordinary secrecy surrounds the new book, which began as a script Harris wrote for a film that is out on general release in February next year. A worldwide embargo means that no proof copies are being sent out in advance of publication on 5 December. Harris, as ever, will be doing no interviews. Everything we need to know about him or his characters is there in the fiction. 'You must understand that when you are writing a novel, you are not making anything up. It's all there and you just have to find it,' he once said.

The profound mystery of the first two Lecter novels, Red Dragon (1981), in which the doctor appears only as a minor character, and in prison at that, and The Silence of the Lambs (1988), was that no psychological explanation was offered for his extreme cruelty. He was beholden to no one and seemed to have come from nowhere. 'Nothing happened to me,' he tells Clarice Starling, the investigator whose mission it becomes to trap him. 'I happened. You can't reduce me to a set of influences.'

But this, it seems, is exactly what Harris is now attempting to do: to reduce Lecter to a set of influences, to show how he became the man he is, without conscience or remorse. Recently, an extract from Hannibal Rising was posted on his official website, where you can also hear Harris reading from the book in his well-modulated, Deep South-inflected voice.

In Hannibal (1999), the third novel in the series, Harris had already begun to complicate and deepen Lecter's story and, thus, fleetingly, to explain him. As it turns out, Lecter did in fact come from somewhere after all - from eastern Europe, the son of Lithuanian aristocrats (he is a cousin of the artist Balthus). His childhood was marked by trauma and loss, not least when he witnessed the torture and murder of his only sister, Mischa, by army deserters.

All this was only hinted at, in sepia-tinted flashback, in Hannibal. Now, the full horror of his early suffering is to be revealed in garish Technicolor, as are the secrets of how, as a young boy, Lecter became mute and how his highly refined aesthetic sensibility was nurtured by a Japanese aunt.

What is going on here? Why is Harris, who delighted for so long in withholding so much about his diabolical creation, now prepared to tell all, at the risk, perhaps, of losing much of his readership?

'I'm not sure why he's doing this,' says David Sexton, author of the fine critical study, The Strange World of Thomas Harris. 'I know he gives a lot of thought to backstory and motive. I know he is interested in the dominant frames in people's lives. I have read the extract on his website and, I'm afraid, it's catastrophic. I believe in Harris as a writer and I'm sure there will be good things in the new book, but what we have so far is a disaster. He knows a great deal about crime and America, but when it comes to aristocracy in Ukraine he is, well, less secure.'

Thomas Harris was born in 1940 in Jackson, Tennessee, the only child of an electrical engineer of modest means who died in 1980. Harris, according to his agent and friend Mort Janklow, remains close to his elderly mother, Polly. She once spoke of how her son called her every night, no matter where he was, and often discusses with her particular scenes from his work-in-progress, which, she added, shortly before the publication of Hannibal, often 'kept her awake at night'. As a boy, growing up in the small town of Rich, Mississippi, in the Deep South, Harris was withdrawn and isolated and, above all, an obsessive reader, if not yet also writer.

After graduating from Baylor, a Baptist university in Waco, Texas, where he studied English, he worked as a reporter on a local newspaper. In the late Sixties, following divorce from his first and only wife (there is a daughter from the marriage), he moved to New York to take up a job at Associated Press. There, he excelled as a crime reporter, showing an unusual curiosity in the finer details and nuances of the crimes he wrote about, no matter how bleak. 'He was a great reporter,' says Janklow, with forgivable loyalty. 'He has an intimate knowledge of police procedure and of homicide investigations and, indeed, of the psychology of the murderer.'

In 1975, Harris published his first novel, Black Sunday, a rather conventional thriller about a spectacular plot by terrorists to commit mass murder during the Super Bowl in Miami. The book was no more than a minor success until it was sold to Hollywood, as were, respectively, each of Harris's subsequent novels, Red Dragon, The Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal and, now, Hannibal Rising. The sale of the film rights of Black Sunday freed Harris from journalism to become a dedicated writer of fiction.

He writes slowly, partly because his books are so fastidiously researched and so dense in arcane reference, but also because, as his fellow bestselling novelist Stephen King has remarked, the very act of writing for him is a kind of torment - King speaks of Harris writhing on the floor in agonies of frustration.

A whole industry exists around Lecter and, by implication, his creator. Harris's early fascination with criminal psychology, forensic pathology and the hard technology of modern police procedure has spawned countless inferior imitators. The films of his books, notably Michael Mann's superbly stylised Manhunter (an adaptation of Red Dragon) and Jonathan Demme's multiple Oscar-winning The Silence of the Lambs, were, for a time, among the most influential in Hollywood.

Today, Harris is one of the most privileged writers in the world and one of the best rewarded. There is for him none of the usual delay between delivery of a manuscript and its publication. Nor is there much editorial interference.

'I did not receive Hannibal Rising until mid-September,' says his British editor Jason Arthur, 'and we are publishing it in December. Not bad.'

'Listen,' says Janklow, 'his books never really need any editing. What he delivers has the quality of a precisely cut gem.'

Today, Harris lives with his long-time partner, a former publishing editor called Pace Barnes, in south Florida. He has a second house, on Long Island, where he spends the summer, and he travels as often as he can to Europe, with Paris being a favourite city.

He remains reclusive, but is seldom morose, even though he is so often alone, working in an office separate from his house, in quite an isolated setting.

'He sits in that office, for days at a time, not even writing a word,' Janklow told me. 'It's the intimacy of the details that he's after.'

How strange is Thomas Harris?

'He's one of the good guys,' Janklow says, as you might if you were taking a 15 per cent cut of his earnings. 'He is big, bearded and wonderfully jovial. If you met him, you would think he was a choirmaster. He loves cooking - he's done the Cordon Bleu exams - and it's great fun to sit with him in the kitchen while he prepares a meal and see that he's as happy as a clam. He has these old-fashioned manners, a courtliness you associate with the South.'

And yet there is darkness in the life: imaginative rather than actual, perhaps, but darkness all the same. Janklow speaks of Harris having to carry these 'terrible burdens'. It must indeed be a terrible burden to be drawn ceaselessly to murder, violence and suffering, to what is worst in the human story.

Harris often speaks as if he has no control over Lecter, as if the doctor exists in his own realm, beyond good and evil. Lecter, he once said, 'is probably the wickedest man I've heard of; at the same time, he tells the truth and he says some things that I suppose we would all like to say'.

Is this why Harris is now expending so much labour on revealing the vulnerability and weakness of Lecter, because he tells the truth?

Martin Amis, an admirer of the early books, is one of several notable writers who believes that Harris is in the process of destroying his literary reputation; that, as he put it, he has 'gone gay on' Lecter.

To translate: he likes him too much, as does evidently Harris's agent, if only because the curious popularity of the not-so-good doctor proves that crime pays very handsomely indeed, if you write well enough about it.

'Let me tell you this,' Janklow says. 'Once you've read the new book and seen the film, you will feel real sympathy for Hannibal Lecter.'

Let's see.

The Harris lowdown

Born

1940 in Jackson, Tennessee. An only child, his father was an electrical engineer and his mother a teacher. He attended Baylor University in Waco, Texas and while there worked as a reporter for the local newspaper, the Waco Tribune-Herald, covering crime.

Best of times

The brouhaha around the publication of Hannibal, the feverishly anticipated follow-up to The Silence of the Lambs. Film rights were sold for £5.5m and Anthony Hopkins and Jodie Foster, who both won Oscars for their performances in the 1991 film of The Silence of the Lambs, were apparently keen to get their teeth into the new script (it would, however, be Julianne Moore who ended up playing FBI agent Clarice Starling this time round).

Worst of times

Possibly his childhood. He was, apparently, a withdrawn and isolated child who took refuge in books. Or maybe when a journalist suggested it took a psychopath to write about one. He hasn't spoken to the press since.

What he says (about Hannibal Lecter)

'He's immensely amusing company. I work in this little office and I'm always glad when he shows up.'

What others say

'Probably the most non-violent man I've ever known... he's very retiring. He hardly ever goes to parties.'

By James Coleman, his uncle