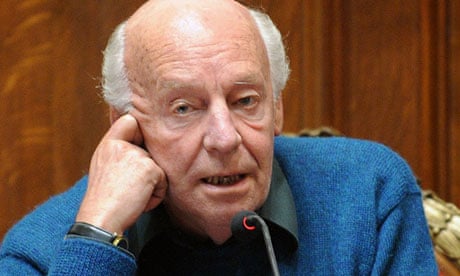

Most mornings it's the same. At the breakfast table Uruguayan-born author, Eduardo Galeano, 72, and his wife, Helena Villagra, discuss their dreams from the night before. "Mine are always stupid," says Galeano. "Usually I don't remember them and when I do, they are about silly things like missing planes and bureaucratic troubles. But my wife has these beautiful dreams."

One night she dreamt they were at an airport where all the passengers were carrying the pillows they had slept on the night before. Before they could board officials would run their pillows into a machine that would extract the dreams from the night before and make sure there was nothing subversive in them. When she told him he was embarrassed about the banality of his own. "It's shaming, really."

There is not much magical about Galeano's realism. But there is nothing shaming in it either. This septuagenarian journalist turned author has become the poet laureate of the anti-globalisation movement by adding a laconic, poetic voice to non-fiction. When the late Hugo Chávez pressed a copy of Galeano's 1971 book Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent into the hands of Barack Obama before the world's press in 2009, it leapt from 54,295th on Amazon's rankings to second in just a day. When Galeano's impending journey to Chicago was announced at a reading in March by Arundhati Roy, the crowd cheered. When Galeano came in May it was sold out, as was most of his tour.

"There is a tradition that sees journalism as the dark side of literature, with book writing at its zenith," he told the Spanish newspaper El Pais recently. "I don't agree. I think that all written work constitutes literature, even graffiti. I have been writing books for many years now, but I trained as a journalist, and the stamp is still on me. I am grateful to journalism for waking me up to the realities of the world."

Those realities appear bleak. "This world is not democratic at all," he says. "The most powerful institutions, the IMF [International Monetary Fund] and the World Bank, belong to three or four countries. The others are watching. The world is organised by the war economy and the war culture."

And yet there is nothing in either Galeano's work or his demeanour that smacks of despair or even melancholy. While in Spain during the youth uprisings of the indignados two years ago, he met some young protesters at Madrid's Puerta del Sol. Galeano took heart from the demonstrations. "These were young people who believed in what they were doing," he said. "It's not easy to find that in political fields. I'm really grateful for them."

One of them asked him how long he thought their struggle could continue. "Don't worry," Galeano replied. "It's like making love. It's infinite while it's alive. It doesn't matter if it lasts for one minute. Because in the moment it is happening, one minute can feel like more than one year."

Galeano talks like this a lot – not in riddles, exactly, but enigmatically and playfully, using time as his foil. When I ask him whether he is optimistic about the state of the world, he says: "It depends on when you ask me during the day. From 8am until noon I am pessimistic. Then from 1pm until 4 I feel optimistic." I met him in a hotel lobby in downtown Chicago at 5pm, sitting with a large glass of wine, looking quite happy.

His world view is not complicated – military and economic interests are destroying the world, amassing increasing power in the hands of the wealthy and crushing the poor. Given the broad historical sweep of his work, examples from the 15th century and beyond are not uncommon. He understands the present situation not as a new development, but a continuum on a planet permanently plagued by conquest and resistance. "History never really says goodbye," he says. "History says, see you later."

He is anything but simplistic. A strident critic of Obama's foreign policy who lived in exile from Uruguay for over a decade during the 70s and 80s, he nonetheless enjoyed the symbolic resonance of Obama's election with few illusions. "I was very happy when he was elected, because this is a country with a fresh tradition of racism." He tells the story of how the Pentagon in 1942 ordered that no black people's blood be used for transfusions for whites. "In history that is nothing. 70 years is like a minute. So in such a country Obama's victory was worth celebrating."

All of these qualities – the enigmatic, the playful, the historical and the realist – blend in his latest book, Children of the Days, in which he crafts a historical vignette for each day of the year. The aim is to reveal moments from the past while contextualising them in the present, weaving in and out of centuries to illustrate the continuities. What he achieves is a kind of epigrammatic excavation, uprooting stories that have been mislaid or misappropriated, and presenting them in their full glory, horror or absurdity.

His entry for 1 July, for example, is entitled: One Terrorist Fewer. It reads simply. "In the year 2008, the government of the United States decided to erase Nelson Mandela's name from its list of dangerous terrorists. The most revered African in the world had featured on that sinister roll for 60 years." He named 12 October Discovery, and starts with the line: "In 1492 the natives discovered they were Indians, they discovered they lived in America."

Meanwhile 10 December is called Blessed War and is dedicated to Obama's receipt of the Nobel prize, when Obama said there are "times when nations will find the use of force not only necessary, but morally justified." Galeano writes: "Four and a half centuries before, when the Nobel prize did not exist and evil resided in countries not with oil but with gold and silver, Spanish jurist Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda also defended war as 'not only necessary but morally justified'."

And so he flits from past to present and back again, making connections with a wry and scathing wit. His desire, he says, is to refurbish what he calls the "human rainbow. It is much more beautiful than the rainbow in the sky," he insists. "But our militarism, machismo, racism all blinds us to it. There are so many ways of becoming blind. We are blind to small things and small people."

And the most likely route to becoming blind, he believes, is not losing our sight but our memory. "My great fear is that we are all suffering from amnesia. I wrote to recover the memory of the human rainbow, which is in danger of being mutilated."

By way of example he cites Robert Carter III – of whom I had not heard – who was the only one of the US's founding fathers to free his slaves. "For having committed this unforgivable sin he was condemned to historical oblivion."

Who, I ask, is responsible for this forgetfulness? "It's not a person," he explains. "It's a system of power that is always deciding in the name of humanity who deserves to be remembered and who deserves to be forgotten … We are much more than we are told. We are much more beautiful."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion