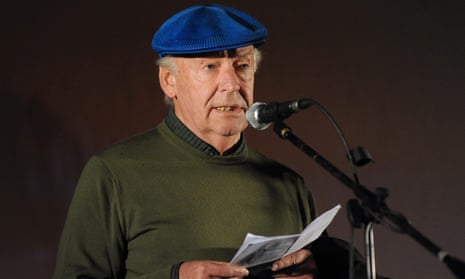

The Uruguayan author and journalist Eduardo Galeano, one of Latin America’s leading anti-capitalist voices, has died of cancer at the age of 74 in Montevideo.

His death on Monday was confirmed by the weekly publication Brecha, where he was a contributor.

“The world and Latin America have lost a maestro of the liberation of the people,” said Bolivian president Evo Morales. “His messages and works have always been oriented towards defending the sovereignty and dignity of our peoples.”

Galeano was best known for his 1971 book Open Veins of Latin America, which rocketed to the top of US bestseller lists after the Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez presented a copy to President Barack Obama in 2009.

Subtitled “Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent” the book argues that Latin America has been consistently impoverished in order to feed the prosperity of Europe and the US.

In his chronicle of centuries of economic exploitation, Galeano wrote: “The human murder by poverty in Latin America is secret. Every year, without making a sound, three Hiroshima bombs explode over communities that have become accustomed to suffering with clenched teeth.”

The book, which established Galeano as one of the region’s most prominent writers, became a rallying cry among leftist circles, and was banned during periods of military leadership in Chile, Argentina and Uruguay. A recent edition included an introduction by novelist Isabel Allende, who once said the book was one of the few items she brought along when she fled Chile after the military coup in 1973.

However, Galeano himself later admitted to mixed feelings about the book. “[It] was trying to be a work of political economics, but I just didn’t have the right training. I don’t regret writing it, but I’ve moved beyond that stage.”

When asked by reporters about Chávez’s gift to Obama, Galeano noted that the late Venezuelan president had presented his US counterpart with a Spanish edition of the book. “He gave it to Obama with the best intentions in the world, but he gave it to Obama in a language that he doesn’t know. So it was a generous gesture, but a bit cruel,” he said.

Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff said Galeano’s death was a “big loss” particularly for those fighting for a “Latin America that is more inclusive, just and united.”

In a statement she added, “May his work and example of struggle stay with us and inspire us each day to build a better future for Latin America.”

“Eduardo Galeano, Uruguayan writer and dear friend,” Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa wrote on twitter. “Latin America’s veins are open in your name,” while Greece’s Alexis Tsipras noted that the death of Galeano affected “every citizen of Europe.”

During a career that spanned half a century, Galeano wrote dozens of works of fiction and non-fiction, with several of them being translated into as many as 20 languages.

He began working as a journalist in the 1960s, editing Marcha, one of Latin America’s top political and cultural weeklies. In 1973, following a military coup, he fled to Argentina and started a similar review called Crisis. When Argentina’s military dictatorship began its ‘dirty war’ against leftists, he took exile in Spain.

Later in life, he also won acclaim for his book on another of his passions, football. His 1995 celebration of the beautiful game, Football in Sun and Shadow, led the Guardian’s Richard Williams to laud him as “the Pelé of football writing”.

In 2013, speaking to the Guardian about his latest book, Children of the Days, Galeano detailed a world where power and wealth were becoming increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few, weaving in examples from the 15th century to the present day. “History never really says goodbye,” he said at the time. “History says, see you later.”

It was a stance that permeated his writing, he told reporters, describing himself as a “writer obsessed with remembering, with remembering the past of America and above all that of Latin America, intimate land condemned to amnesia”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion