In the aftermath of Brazil’s 7-1 defeat at the hands of Germany in Belo Horizonte last July, the man I wanted to hear from was Eduardo Galeano. No one had more interesting things to say about the South American passion for football. But if he wrote about the trauma induced by that thrashing, nobody translated it into English. Either way, it was a loss.

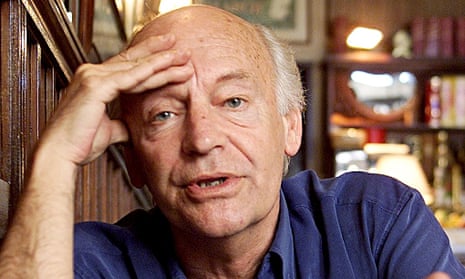

Galeano died this week in Montevideo, his birthplace, aged 74. He was widely mourned as a great historian and novelist but none of the obituaries failed to mention that he was also the author of Football in Sun and Shadow. First published in translation in 1997, it established itself as a firm favourite among a certain kind of reader of the game’s literature.

He had been nine years old when Brazil suffered an earlier football trauma at the hands of his own compatriots in the 1950 World Cup final. “Like every other Uruguayan,” he wrote, “I was glued to the radio. When the voice of Carlos Solé broadcast the melancholy news of Brazil’s first goal, my heart sank to the floor. Then I turned to my most powerful friend. I promised God a heap of sacrifices if He would appear in the Maracanã and change the course of the game.

“I never managed to remember all those promises, so I couldn’t keep them. Besides, although Uruguay’s victory was certainly a miracle, it was the work of a flesh-and-blood mortal named Obdulio Varela, who carried the entire team on his shoulders. At the end of the game, reporters surrounded the hero. Obdulio didn’t stick out his chest or boast about being the best. ‘It was one of those things,’ he murmured, shaking his head. And when they wanted to take his picture, he turned his back.

“The next day he dodged the crowd at Montevideo airport, where his name hung in lights. In the midst of the euphoria he slipped away, dressed like Humphrey Bogart in a raincoat with the lapels turned up and a fedora pulled down to his nose. The top brass of Uruguayan football rewarded themselves with gold medals. They gave the players silver medals and some money. Obdulio’s prize money was enough to buy a 1931 Ford. It was stolen a week later.”

When intellectuals or people from the world of the arts start writing about football, the results are sometimes rewarding, sometimes not. In England, the great art critic David Sylvester contributed match reports to the Observer in the 1960s. The poet Ian Hamilton produced an interesting fan-portrait of Paul Gascoigne in Gazza Agonistes, published in 1998. The novelist AS Byatt, a Booker prize winner, wrote about Euro 2008 for the Observer, describing Michael Ballack’s face after scoring as goal as “a distorted mask of focused breathing energy, like a classical sculpture of a wind god”.

But throughout the 60s there were also regular pieces in various periodicals – including the Spectator and the Listener – by Hans Keller, an Austrian musician and critic who had escaped the Nazis in 1938 and became a prominent figure in the cultural life of postwar Britain. Keller was critical of Alf Ramsey before the 1966 World Cup, believing his tactics to be aimed at suppressing individuality (and in particular that of his beloved Jimmy Greaves). His composition Football Variations, for violin, cello and piano, called upon the performers to shout “Goal!” and “Offside!”, and his obsession with the game made him a regular target of Private Eye’s unsparing satirists.

Although Galeano was a certified intellectual, his readers were never in doubt of the warmth of the blood running through his veins. Of a great German forward he wrote: “A jolly face. You couldn’t imagine him without a mug of foaming beer in his fist. On Germany’s football pitches he was always the shortest and stoutest. But Uwe Seeler was a flea when he jumped, a hare when he ran, and a bull when he headed the ball.”

He often celebrated the achievements of black players, including Arthur Friedenreich, whose goal for Brazil deprived Uruguay of the South American championship in 1919. “This green-eyed mulatto founded the Brazilian style of play,” he wrote. “Friedenreich brought to the solemn stadium of the whites the irreverence of brown boys who entertained themselves fighting over a rag ball in the slums. Thus was born a style open to fantasy, one that prefers pleasure to results. From Friedenreich onwards, there have been no right angles in Brazilian football, just as there are none in the hills of Rio de Janeiro or the buildings of Oscar Niemeyer.”

He loved football for its ability to survive corruption and maladministration. More than 20 years ago he was pouring scorn on one Joseph Blatter, “a Fifa bureaucrat who never once kicked a ball but goes about in a 25-foot limousine driven by a black chauffeur”.

His socialist heart perhaps prevailed over his good sense when he welcomed the attempt of a group of prominent players, led by Diego Maradona, to form a trade union. “The fact is that professional players offer their labour to the factories of spectacle in exchange for a wage,” he wrote. “The price depends on performance, and the more they get paid, the more they are expected to produce. Squeezed to the last calorie, they’re treated worse than racehorses. Racehorses? Paul Gascoigne likes to compare himself to a factory-raised chicken: controlled movements, rigid rules, set behaviours that must always be repeated.”

This was before the era of the £50,000-a-week teenage footballer. It would have been interesting to hear his views on that phenomenon, and on Luis Suárez, another compatriot, whose behaviour reflects all the skill, violence and garra (fighting spirit) that characterise Uruguayan football.

Towards the end of the book, Galeano recounted the question posed by a reporter to the German theologian Dorothee Sölle: “How would you explain to a child what happiness is?” “I wouldn’t explain it,” she replied. “I’d toss him a ball and let him play.”

“Professional football,” Galeano added, “does everything to castrate that energy of happiness, but it survives. And maybe that’s why football never stops being astonishing. As a friend says, that’s the best thing about it – its stubborn capacity for surprise. The more the technocrats programme it down to the smallest detail, the more the powerful manipulate it, football continues to be the art of the unforeseeable. When you least expect it, the impossible occurs: the dwarf teaches the giant a lesson, and a scraggy, bow-legged black man makes an athlete sculpted in Greece look ridiculous.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion