The fact that developer Double Fine Productions has chosen to remaster the classic 1995 point-and-click adventure Full Throttle isn’t in itself remarkable. The LucasArts titles of the mid-1990s are widely loved and celebrated, and we have already seen updates of stablemates Grim Fandango and Day of the Tentacle.

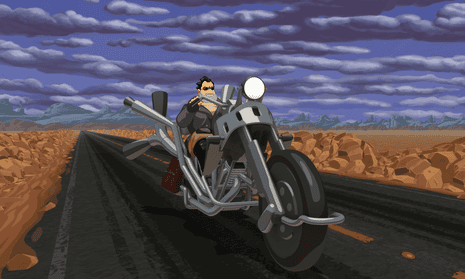

What is remarkable is that the strength of the narrative design, silly gags and beautiful vistas hasn’t diminished at all. Holding a PS4 controller in front of the new version, it’s obvious that the 20-year-old game is 10 times more ambitious than most commercially-made video games today. Not in the action of the game, in which your biker man Ben merely solves increasingly obscure puzzles involving the collection and application of objects to scenery (most memorably illustrated in the classic command “Slam face on bar”). No. What makes its legacy is something much more interesting than how many puzzles the game has, or how difficult they are to solve.

The game’s designer, Tim Schafer, said that during Full Throttle development at LucasArts he worked down the corridor from his friend Hal Barwood, who was working on the Indiana Jones games (Barwood’s Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is also an excellent adventure). Schafer must also have been breathing in the creative fumes from sister company LucasFilm, situated not too far away. Full Throttle is, after all, the rough-and-tumble action matinee equivalent of Raiders Of The Lost Ark in terms of its pulp demeanour, scrapes and gags – though the game drops the stentorian Williams audio for the raging chords of The Gone Jackals, the local hard rock band that provided the soundtrack. Unlike the Indiana Jones games, Full Throttle had no backstory gifted from a major movie series – and yet it is as humanistic a saga as Spielberg could ever tell. Most games can’t even combine themes of sci-fi and horror well, never mind put Yojimbo, The Road Warrior, and Kurt Vonnegut together in a story where the bad guy is played by Mark Hamill.

Full Throttle is a game fuelled by narrative complexity: it combines diverse themes, characters and relationships, and a strange future California. On their own these elements would not be original, but together they provide a rich, hilarious experience, cynical of technology and alive with interesting conversations, hurtling towards a revenge denouement.

There’s a humorous country song about the apocalypse that plays in a character’s trailer called ‘Chitlins, Whiskey and Skirt’. An old biker priest called Father Torque gives you advice about debiking other biker gangs. The dystopian commercialism the game sets itself against culminates in Ben stealing a box full of toys to explode himself across a minefield like something out of a Terry Gilliam animation.

It’s a strange setting, an odd Mad Max land of hovercars, nitro-boosted choppers, and weird cave-dwelling gang-cults. But it’s bound together by something that is very difficult to pull off in games: the narrative pervades every aspect of the medium successfully. The industry standard approach to storytelling is to lead with what the player wants to do in a game, then layer how you should feel about that function onto the canvas afterwards. In Full Throttle however, the sound, the art direction, the character design, the game design, the voice acting, the music, the interface – these are all places you can see have been specifically designed to tell you something about the story world.

Full Throttle examines how gallant, restrained masculinity could function as an action-adventure ideal using every material available. The ways the player can interact with given situations are designed to inform them of Ben’s values. Take the thing you see most often: the adventure game verb interface. Click it to see a Hell’s Angel style skull tattoo, consistently on fire, and the display of Ben’s major actions: eyeball, talk, grab and kick. That’s the kind of guy Ben is - eyeball, talk, grab and kick. Here, the story is informing how the game is played. It’s a game about rough-housing and making do, not intellectualising, and even at my reachiest, I would still maintain that the notorious puzzle in which you have to kick a crack in a brick wall at just the right time - well, the ruggedness of merely kicking a brick wall for hours is in keeping. It’s thematic. It’s who Ben is.

People might complain that the remaster has made some art more cartoony – this is true, but much has also been preserved, and you can always switch back to the original art in the menu if you prefer. People might complain that the puzzles have not improved with age, and that having to search through each menu on an old aeroplane carcass to find the right machine gun command over and over in a timed scene is tiresome: but I’d say to you, so is learning how to avoid being floored in Dark Souls every time. We all come back to a game for that certain friction, and that certain reward, it just depends what those rewards are. The rewards of Ben getting back on his bike to a remastered Gone Jackals bass line are so very high, and painstakingly negotiating into an explosive cutscene is just as good as you might remember. The unobtrusive hints system also provides an added relief, something that I didn’t have playing this game through at eleven years old.

If nothing else, the commentary option, where Schafer and the team hazily ramble on about about the development process (“was I here for that time that the cat made that unreproducable bug”, “remember when we parked a Harley in the LucasArts lobby all night so we could tape record sounds from it”) makes it worth downloading and playing through, one more time, particularly on a large screen with good speakers. You may also end up studying the lyrics to The Gone Jackals track Legacy again, and think that the dystopian austerity they describe is disturbingly relevant. As is Maureen Corley being usurped from her rightful leadership role by a frightening despot with a fluffy comb-over.

Disclosure: Cara Ellison is a narrative designer who played three boardgames with Tim Schafer at the Double Fine offices this year during the Game Developers Conference.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion