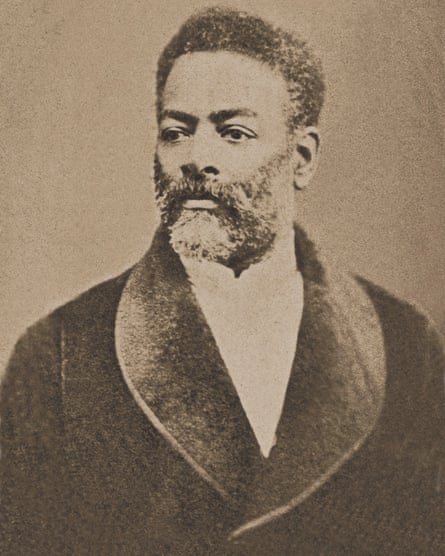

Born in 1830 to a trafficked African woman who escaped enslavement and led uprisings, Luiz Gama defied fate and the Brazilian empire to become the country’s first Black lawyer and a leading abolitionist.

When he was 10 his father, a Portuguese nobleman, illegally sold him into slavery to pay off gambling debts. Gama regained his freedom as a young adult and having learnt to read, became a writer, intellectual and self-taught lawyer. He founded newspapers defending abolition and used the law to help free more than 500 enslaved people before Brazil finally abolished slavery in 1888, six years after he died.

Nearly a century and a half later, the struggle Gama represents has taken centre stage at Rio de Janeiro’s carnival in the official parade of Portela, one of the city’s most storied samba schools.

Portela’s samba-enredo theme song this year was based on Um Defeito de Cor (A Colour Defect), Ana Maria Gonçalves’ seminal novel about the legacy of slavery in Brazil which fictionalises the story of Gama’s mother, Luiza Mahin (named Kehinde in the book). The song, which shares the book’s title, imagined Gama recounting his mother’s life of resistance in powerful lyrics that were belted out by 2,800 performers and about 70,000 spectators during the school’s 67-minute procession down the Sambadrome on Monday night.

“We are remembering Luiz Gama to remind a large part of the population that their life has a history, an origin, roots that must always be remembered,” said Portela’s president, Fábio Pavão.

This is a history that was long silenced in the majority-Black country. “The Brazilian state buried Gama’s work,” said Bruno Lima, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory in Frankfurt who started studying the abolitionist as a teenager two decades ago.

Gama gained some recognition in recent years as Brazil began facing up to its past. In 2018 his name was inscribed in the Book of Heroes and Heroines of the Nation (Mahin’s was added a year later). An anthology of his writings, edited by Lima, has been published and a room has been named after him at the University of São Paulo’s law school, where he was prevented from formally studying due to his race.

He has now been celebrated in the greatest show on earth, as Portela’s carefully choreographed procession featured four separate incarnations of Gama atop elaborate floats.

Lima, who later this month is launching a book on the man he considers “one of the greatest thinkers of modern times”, hoped “Portela will raise Gama to a new level in popular historical knowledge”.

Behind the extravagant spectacle and semi-naked dancers, carnival processions have historically been vehicles for showcasing Afro-Brazilian culture and shining a light on sidelined stories.

“Samba schools have always played an educational role. They are very effective at popularising unknown characters and stories,” said Mauro Cordeiro, a researcher on carnival at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

“Samba schools are fundamentally political organisations … [and] samba processions are a great sounding board for [contemporary] debates,” he added.

This year, at least half of Rio’s top-tier schools dedicated their samba song to Afro-centred themes, which is not unusual but shows “the importance of this type of narrative in the festivities”, Cordeiro said. These included Estação Primeira de Mangueira, celebrating the beloved singer Alcione with a samba titled A Negra Voz do Amanhã (The Black Voice of Tomorrow), and Paraíso do Tuiutí, which told the story of João Cândido, a sailor who led a revolt against floggings in 1910 and whose descendants are demanding reparations from the Brazilian state.

Portela has also engaged with these debates outside of carnival. Last November, the school hosted a public hearing to discuss reparations for slavery, during which the top bank Banco do Brasil apologised for the institution’s role in the slave economy following an investigation into these historical links.

These issues echoed around Portela’s blue-and-white headquarters last week as hundreds of people crammed into its home in Rio’s northern suburbs for a final rehearsal. “This year’s theme feels really important because I’m Black, so it represents my race,” said lifelong portelense Roseli Santos, 61, before taking her place in a line of performers sporting uniformed T-shirts emblazoned with the samba’s title, A Colour Defect.

As the thump and clang of the percussion instruments filled the hall with a rousing beat, the dancers threw up their arms as one and intoned the chorus celebrating Mahin, Gama and their shared struggle: “Hail Kehinde! Your name lives on! Your people are free! Your son has prevailed!”